The people of Ukraine have suffered much to preserve their Catholic Faith through the ages.

In recognition of those of our MAGNIFICAT readership who worship in the Byzantine liturgical tradition, we seek here to explore the traditions of Lent and Holy Week as observed by Byzantine Rite Catholics of Ukraine.

A Season of Preparation

For Ukrainians, Lent is a time of reconciliation with God and with one’s neighbor. The faithful strive to receive the sacrament of penance. Contending relatives and neighbors are urged to make peace with one another. The liturgical rites of this penitential season are punctuated by acts of reverence known as poklony, the “prostrations of Saint Andrew.” The faithful kneel and bow their foreheads to the floor. This prostration, performed in series of three, expressing remorse for one’s sins, is a plea for reconciliation with God. During Lent Ukrainians also remember the faithful departed, praying for them at a liturgical service called the sorokousty (“forty mouths”), a title stemming from the origin of this rite as a supplication for the dead offered by forty monks praying in unison.

For Ukrainians, Lent is a time of reconciliation with God and with one’s neighbor. The faithful strive to receive the sacrament of penance. Contending relatives and neighbors are urged to make peace with one another. The liturgical rites of this penitential season are punctuated by acts of reverence known as poklony, the “prostrations of Saint Andrew.” The faithful kneel and bow their foreheads to the floor. This prostration, performed in series of three, expressing remorse for one’s sins, is a plea for reconciliation with God. During Lent Ukrainians also remember the faithful departed, praying for them at a liturgical service called the sorokousty (“forty mouths”), a title stemming from the origin of this rite as a supplication for the dead offered by forty monks praying in unison.

Preparations for Easter climax with Holy Week, known among the Ukrainians as the “Great Week.” On Palm Sunday in Ukraine, pussy willow branches are blessed and distributed in place of palms. This rite is observed not at the beginning of Mass, but rather at the morning service of the Byzantine divine office known as Orthros. Afterward, observing a tradition of the day referred to as Boze Rany (“God’s Wounds”), Ukrainians gently tap each other with the blessed branches in remembrance of the scourging of Christ. By Wednesday of Holy Week, Ukrainian women are completing the task they began during Lent, that of painting and decorating their renowned Easter eggs, continuing a tradition traceable to the thirteenth century. Ukrainians see the egg as a symbol of the Holy Sepulcher. Some of the eggs, the krashanky, are painted in a solid color, especially red. The others, the pysanky, are adorned with an intricate array of symbols and designs. A net-like hatched pattern symbolizes the fisherman’s net of Christ and his Apostles as fishers of men. A pattern of dots on the egg represents the tears of the Blessed Virgin Mary, mourning for her divine Son. A ladder symbolizes the ascent to heaven that those late in life are soon to make. When beginning the decoration of these eggs, Ukrainian women make the sign of the cross and whisper the supplication, “God help me” or “God bless and help us.”

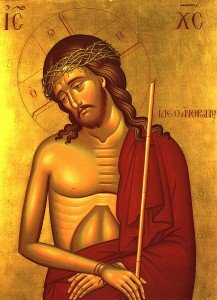

Contemplating the Passion

On Holy Thursday, the ceremonial washing of the feet of twelve men is observed in Ukrainian cathedrals and monasteries. In parishes across Ukraine, the most distinctive rite of Holy Thursday in the Byzantine liturgy is celebrated in the evening, the strasti service. This ceremony, which is actually the Byzantine morning office (Orthros) for Good Friday observed in an anticipatory manner on the preceding evening, consists of twelve Gospellections relating the complete account of the Passion of Christ from the four Evangelists. These readings are accompanied by poetic hymns and antiphons that serve as profound reflections upon the events of Holy Thursday night and Good Friday. Bells are rung after each Gospel reading, and the people offer their homage to Christ with the poklony prostrations. In some Ukrainian parishes, twelve candle-bearers are present for this service. As each Gospellection is completed, one of the candle-bearers departs an action representing the Apostles’ desertion of Christ in Gethsemane. The bells are silenced following the last Gospel, and wooden clappers take their place until Easter morning.

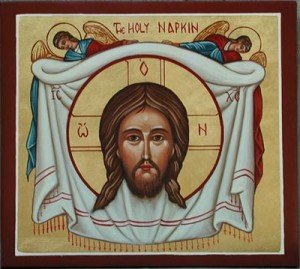

On Good Friday, parishes gather for another office of readings and hymns, the “Great Hours.” Like the strasti service of the preceding night, this office presents the Gospel accounts of the Passion. The veneration of the cross, which began in fourth-century Jerusalem, subsequently disappeared from the Eastern liturgy of Good Friday. In its place has arisen what is perhaps the most visually expressive observance of Byzantine Holy Week practices in Ukraine and elsewhere: the veneration of the epitaphios, in Ukrainian the plaschenytsia, a cloth representing the burial shroud of Christ, embroidered with an image of Christ resting in death. Although the custom as it now exists cannot be dated back further than the sixteenth century, the Eastern tradition of commemorating the burial of Christ toward the end of the Good Friday liturgy is traceable in one form or another to fourth-century Jerusalem. In the fifth- to eighth-century Georgian Lectionary, a liturgical book of Jerusalem, there was a ceremonial washing of a relic of the true cross clearly intended to represent the washing of Christ’s body for his burial. In the present-day Byzantine liturgy of Ukrainian Catholics, the plaschenytsia is carried twice on Good Friday, first at the end of Vespers and again in the night, during the office of Orthros for Holy Saturday, which has been advanced to Good Friday. The second procession circles the outside of the church before entering it. Several elders of the parish carry the plaschenytsia, preceded by parishioners bearing a crucifix and banners. After the plaschenytsia, the priest follows, bearing the Eucharist, with the rest of the faithful accompanying from behind. Inside the church, the cloth is laid upon a representation of the Holy Sepulcher, which is adorned with palms, flowers, and candles. Each worshiper advances on his knees to the shroud, and making the sign of the cross, kisses each of the five wounds of Christ depicted on the cloth before withdrawing on his knees. Afterward, parishioners maintain a continual watch before the Holy Sepulcher, with the faithful taking turns as guards of honor from Good Friday through Holy Saturday.

Celebrating the Resurrection

![]() The Easter Vigil of the Byzantine Rite is celebrated in an anticipatory manner on Holy Saturday morning. This extraordinarily advanced timing of the vigil, well before Easter night, has led many Byzantine Catholics, including those of Ukraine, to view a second liturgical rite of Easter, the combined Mass and office of Orthros for Easter Sunday morning, begun at midnight, as the primary celebration of the Easter solemnity. In Ukraine, this liturgy of Easter night begins with an outdoor procession. The priest and the people walk around the perimeter of the church three times, with the plaschenytsia carried as on Good Friday. The procession then halts before the closed church doors, where the priest intones the chant “Khrystos voskres” (“Christ is risen”). The people respond by repeating the chant. The priest now opens the church doors, and all sing for the third time, “Khrystos voskres.” The faithful then fill the pews for the Mass that follows.

The Easter Vigil of the Byzantine Rite is celebrated in an anticipatory manner on Holy Saturday morning. This extraordinarily advanced timing of the vigil, well before Easter night, has led many Byzantine Catholics, including those of Ukraine, to view a second liturgical rite of Easter, the combined Mass and office of Orthros for Easter Sunday morning, begun at midnight, as the primary celebration of the Easter solemnity. In Ukraine, this liturgy of Easter night begins with an outdoor procession. The priest and the people walk around the perimeter of the church three times, with the plaschenytsia carried as on Good Friday. The procession then halts before the closed church doors, where the priest intones the chant “Khrystos voskres” (“Christ is risen”). The people respond by repeating the chant. The priest now opens the church doors, and all sing for the third time, “Khrystos voskres.” The faithful then fill the pews for the Mass that follows.

After Mass, the priest blesses baskets of food brought by the people containing meats, cheese, butter, bread, horseradish, and the solid-colored krashanky Easter eggs, all of which will be consumed by the faithful as they celebrate Easter in their homes. For Easter each member of a Ukrainian family receives a new article of clothing in honor of the Resurrection of Christ. During Lent and Holy Week, let us all make a fitting preparation for the day when Christ will clothe our corruptible bodies with immortality.