![]() The second Prayer of the Faithful is likewise different in St. Basil’s Liturgy. The words from this prayer are, in my estimation, truly powerful. Two very different phrases are significant: “O God, Who have been pleased in Your mercy and compassion to visit our lowliness” and “grant to our lips confident power of speech so that we may call down the grace of Your Holy Spirit upon the gifts that are about to be offered to You”.

The second Prayer of the Faithful is likewise different in St. Basil’s Liturgy. The words from this prayer are, in my estimation, truly powerful. Two very different phrases are significant: “O God, Who have been pleased in Your mercy and compassion to visit our lowliness” and “grant to our lips confident power of speech so that we may call down the grace of Your Holy Spirit upon the gifts that are about to be offered to You”.

First, the fact that God became incarnate for the sake of our salvation is clearly stressed. Second, that God has, through Jesus, given us the ability to call down the Holy Spirit on our gifts if we truly believe. And last, it is through God’s Spirit – His power – that the gifts are transformed and that Christ is truly in our presence. This clearly speaks to how God operates in time. God the Creator has an idea, His Wisdom and Word makes that idea real – names that idea – and then His Energy – His Spirit – brings the spoken word into existence. It is each of the Persons of the Trinity, by their loving cooperation, that bring and sustain all things in existence.

While the beginning dialogue between the celebrant and the faithful at the beginning of the Anaphora is the same as that in the Liturgy of John Chrysostom, the first priestly prayer is different. I shared some ideas from this prayer in a previous issue.

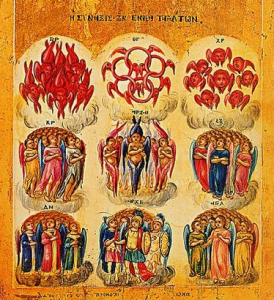

One interesting point in both Liturgies is the fact that neither John nor Basil, when indicating that God is praised by angels, lists nine choirs. Sacred Tradition lists nine choirs in groups of three:

Dominations, Principalities, Powers;

Virtues, Archangels and Angels.

In the versions we use, John only lists four categories of angels and Basil eight. Neither Father mentions Virtues. I shall, in a subsequent issue of the Bulletin, list each of the Choirs and a brief description of the function and role of each choir.

In both Liturgies, we exclaim that what we do, when we celebrate the Liturgy, we do together with the angels of heaven. We declare that we celebrate “with these blessed powers” and cry out with them declaring God to be “holy, indeed most holy.”

The holiness of God is the most difficult of all God’s attributes to explain, partly because it is one of His essential attributes that is not shared, inherently, by man. We are created in God’s image, and we can share many of His attributes, to a much lesser extent. I shall address God’s holiness and the choirs of angels in the future.