The call to holiness is a call to personal salvation! The problem is that, while we have all heard these words, we are not really sure what they mean. They appear to be two words that are intimately connected.

When most people, I believe, think about holiness they think about some of the saints they have heard about and who have achieved perfection, that is no longer prone to mistakes or sins. This understanding, fortunately, cannot be the meaning for this word. Why? Because the Gospels tell us that no one is without sin except God alone and Jesus, the Christ. Perfection is beyond human ability. While it seems that we humans can, during this earthly life, lessen the mistakes we make, being perfect is not possible. So holiness must have a different meaning since we are called to holiness.

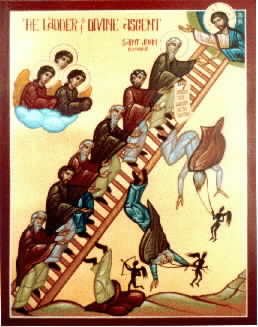

Holiness, in the highest sense, belongs to God and to Christians who are conformed in all things to the will of God. Personal holiness is a work of gradual development. It is carried on under many hindrances, hence the frequent admonitions to watchfulness, prayer and perseverance.

Holiness, then, becomes real when we focus our efforts on developing a genuine relationship with God and attempting to do His will to the best of our ability.

When most humans think of salvation it is my guess that they think that it is something that happens after death, that it means meriting heaven and escaping hell. Salvation, it would seem therefore, is a reward for trying to live a good life.

Salvation for Eastern Christians is the process of attempting to achieve greater union with God by growing in the likeness of Jesus. It is an ongoing, voluntary act by which we seek an entrance to life in Christ here and now. Salvation is something that transpires right now, not after we die.

I am sure that my readers can immediately sense how holiness and salvation are intimately connected.