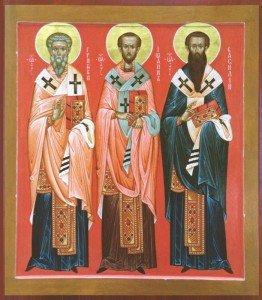

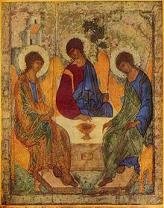

I have been attempting to share with my readers the struggle that the Fathers had around finding the right Greek word to express how it is possible for us to believe that God is Three-In-One and that Jesus is both God and Man. It all rested with the proper use of two Greek words, ousia and, of course, hypostasis.

I have been attempting to share with my readers the struggle that the Fathers had around finding the right Greek word to express how it is possible for us to believe that God is Three-In-One and that Jesus is both God and Man. It all rested with the proper use of two Greek words, ousia and, of course, hypostasis.

The distinction between “ousia” and “hypostasis” is the same as that between the general and the particular; as, for instance, between the animal and the particular man. Wherefore, in the case of the Godhead, we confess one essence or substance so as not to give a variant definition of existence, but we confess a particular hypostasis, in order that our conception of Father, Son and Holy Spirit may be without confusion and clear. If we have no distinct perception of the separate characteristics, namely, fatherhood, sonship, and sanctification, but form our conception of God from the general idea of existence, we cannot possibly give a sound account of our faith. We must, therefore, confess the faith by adding the particular to the common. The Godhead is common; the fatherhood particular. We must therefore combine the two and say, “I believe in God the Father.” The like course must be pursued in the confession of the Son; we must combine the particular with the common and say “I believe in God the Son,” so in the case of the Holy Ghost we must make our utterance conform to the appellation and say “in God the Holy Ghost.” Hence it results that there is a satisfactory preservation of the unity by the confession of the one Godhead, while in the distinction of the individual properties regarded in each there is the confession of the peculiar properties of the Persons. On the other hand those who identify essence or substance and hypostasis are compelled to confess only three Persons, and, in their hesitation to speak of three hypostases, are convicted of failure to avoid the error of Sabellius, for even Sabellius himself, who in many places confuses the conception, yet, by asserting that the same hypostasis changed its form to meet the needs of the moment, does endeavor to distinguish persons.

I realize that this may not be easy to read and, therefore to comprehend since we are talking about a MYSTERY. But I do believe that the Fathers came up with a way to preserve the ONENESS of God while, at the same time, professing belief in God as Trinity.