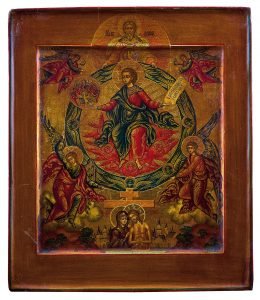

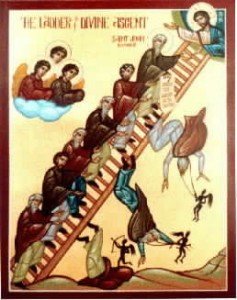

![]() So the Eastern Church sees that the work of Christ, and therefore the Church, is to help humans to develop those positive, Christ-like characteristics that will bring humans to a greater level of communion with the One Who IS Life, God. Holistic healing is thus sought by the Eastern Church with the end of bringing about voluntary and free communion with God. The believer conquers death through participation in God’s Life through the Mysteries (Sacraments) which the Church has been given through the inspiration and power of the Holy Spirit. The Church maintains seven powerful rituals which bring humankind into direct communion with God. Three of the seven are ongoing opportunities given to believers to encounter God and enter into ever-deeper communion with Him: Eucharist, Reconciliation (Penance) and Holy Anointing.

So the Eastern Church sees that the work of Christ, and therefore the Church, is to help humans to develop those positive, Christ-like characteristics that will bring humans to a greater level of communion with the One Who IS Life, God. Holistic healing is thus sought by the Eastern Church with the end of bringing about voluntary and free communion with God. The believer conquers death through participation in God’s Life through the Mysteries (Sacraments) which the Church has been given through the inspiration and power of the Holy Spirit. The Church maintains seven powerful rituals which bring humankind into direct communion with God. Three of the seven are ongoing opportunities given to believers to encounter God and enter into ever-deeper communion with Him: Eucharist, Reconciliation (Penance) and Holy Anointing.

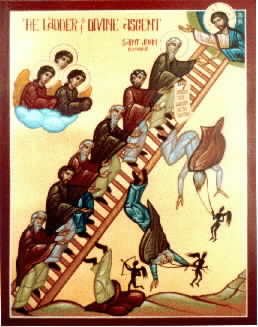

Conversely, the Western understanding of all this essentially declares man “not guilty”, and leaves him, unfortunately, unhealed and unchanged. In the mind of the Eastern Church this distorts the message of Christian salvation: to “be partakers of the divine nature.”

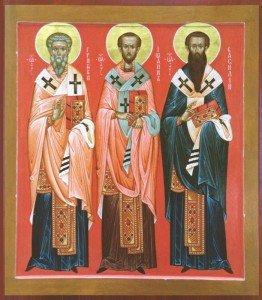

The formation of the Anselmian doctrine of Atonement is seen by modern commentators as “a revolution in theology,” beginning “a new epoch in the theology of Atonement.” This new doctrine stemmed from several factors. Foremost, a characteristic influence of the legalistic Roman mindset that was exhibited in Western theologians as early as Tertullian which encourages and supports a juridical conceptualization concerning the truths of the faith. Anselm drew from Tertullian who sees man’s sin as a disturbance in the “divine order of justice,” and makes penance a “satisfaction to the Lord.”

Another strong influence on Anselm was St. Augustine. Not only did Anselm utilize St. Augustine’s concept of “limited Atonement,” but he also used his methods of theological and philosophical experimentation. St. Augustine, as you will recall, what the Western Father who formulated the idea of Original Sin.