![]() I believe that for the Church, for the world, for mankind there is no more important, more urgent question to be asked that what is accomplished in the eucharist. In reality this question is mot natural to faith, which lives by the thirst for entry into the wisdom of truth, by the thirst for the logical (i.e., reasonable) service of God that manifests and is rooted in the divine wisdom. It is truly the question of the ultimate meaning and purpose of all that is real, of the sacramental ascent to where “God will be all in all,” and thus it is the question that, through faith, was constantly radiating as a mysterious burning in the hearts of the disciples on the road to Emmaus. But that is exactly why it is so important to liberate this urgent question, to cleanse it of everything that obscures, diminishes and distorts it, and this means, first of all, those “questions” and “answers” who depravity lies in the fact that instead of explaining the earthly through the heavenly, they reduce the heavenly and

I believe that for the Church, for the world, for mankind there is no more important, more urgent question to be asked that what is accomplished in the eucharist. In reality this question is mot natural to faith, which lives by the thirst for entry into the wisdom of truth, by the thirst for the logical (i.e., reasonable) service of God that manifests and is rooted in the divine wisdom. It is truly the question of the ultimate meaning and purpose of all that is real, of the sacramental ascent to where “God will be all in all,” and thus it is the question that, through faith, was constantly radiating as a mysterious burning in the hearts of the disciples on the road to Emmaus. But that is exactly why it is so important to liberate this urgent question, to cleanse it of everything that obscures, diminishes and distorts it, and this means, first of all, those “questions” and “answers” who depravity lies in the fact that instead of explaining the earthly through the heavenly, they reduce the heavenly and

the other-worldly to the earthly, to this own “human, only human,” impoverished and feeble “categories.”

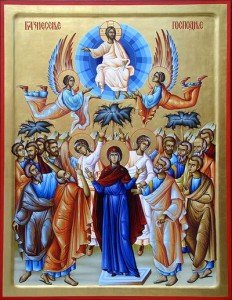

Indeed, with the summons “Let us stand aright. Let us stand in awe. Let us be attentive to offer the holy oblation in peace,” (the beginning of the Anaphora) we actually do enter into the “chief” part of the Divine Liturgy. But it is chief in relation to its other parts, and not in isolation and separation from them. It is chief because in it the entire liturgy finds its fulfillment, everything that it witnesses to, that it manifests, to which it leads and ascends. It begins that sacrament of anaphora (The deliberate repetition of a words or phrases – in this instance the repetition of words of Jesus), that would be impossible without the sacrament of the gathering, the sacrament of offering and the sacrament of unity, but in which – and precisely because it is the fulfillment of the entire liturgy – we are given the understanding of the sacrament that surpasses all comprehension but, nevertheless, manifests all and explains all. It is precisely this “relation,” the wholeness and unity of the eucharistic celebration, that we are reminded of, that we turn our spiritual attention to when the clergy summons us to “stand aright,” to “stand straight” or even to “be good.”

The Divine Liturgy, which is the work of the Church (i.e., people and clergy working together), truly is more than just the change of the bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ.

More to follow!

In discussing the formation of the New Testament (NT), one has to search the writings of the Fathers of the Church. Tradition, which is conveyed by the writings of the Fathers, gives us the context in which the NT was formed. Indeed, patristic citations and lists of books are the two main criteria for judgment of the canon. Yet neither criterion is totally satisfactory. For instance, when Clement of Rome, or Ignatius, or Polycarp cited a book that ultimately was recognized as canonical, just what authority was he giving to this book, since we do not know that the concept of either a NT or a canon was yet formulated? Past discussions simply assumed that these early Fathers had a concept of canonical and non-canonical. And, indeed, even later when there was a concept of a NT, we find strange phenomena in patristic citations. Origen cited 2 Peter at least six times. Yet in his canonical list, he doubted whether 2 Peter should be included. In other words, even a 3rd century, patristic citation of a book ultimately accepted as canonical does not mean that the Father thought it canonical. On the other hand, absence of a citation of a NT book (e.g., during the 2nd century) does not necessarily mean that the Fathers did not know the book or did not consider it of value. There would be little occasion to cite some of the shorter NT works like Philemon and 2-3 John.

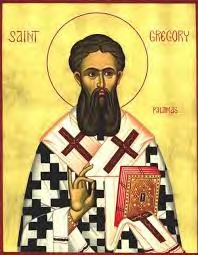

In discussing the formation of the New Testament (NT), one has to search the writings of the Fathers of the Church. Tradition, which is conveyed by the writings of the Fathers, gives us the context in which the NT was formed. Indeed, patristic citations and lists of books are the two main criteria for judgment of the canon. Yet neither criterion is totally satisfactory. For instance, when Clement of Rome, or Ignatius, or Polycarp cited a book that ultimately was recognized as canonical, just what authority was he giving to this book, since we do not know that the concept of either a NT or a canon was yet formulated? Past discussions simply assumed that these early Fathers had a concept of canonical and non-canonical. And, indeed, even later when there was a concept of a NT, we find strange phenomena in patristic citations. Origen cited 2 Peter at least six times. Yet in his canonical list, he doubted whether 2 Peter should be included. In other words, even a 3rd century, patristic citation of a book ultimately accepted as canonical does not mean that the Father thought it canonical. On the other hand, absence of a citation of a NT book (e.g., during the 2nd century) does not necessarily mean that the Fathers did not know the book or did not consider it of value. There would be little occasion to cite some of the shorter NT works like Philemon and 2-3 John. Gregory lays down a crucial principle in his biblical analysis of Proverbs 8:22, “The Lord created me at the beginning of his ways with a view to his works.” Many early Christian exegetes (scholars who study the meaning of biblical texts) saw this text as pointing to the divine Word, “the true Wisdom.” If so, the text appears to text appears to teach that the Son was created, a problem for all who would affirm his timeless, eternal nature. Gregory solves the difficulty by teaching that when biblical texts such as Proverbs speak of the Son as caused or created, they are referring to the economy/dispensation of salvation. The Son, God’s Wisdom, is sent by the Father “with a view to his works,” that is, “our salvation.” Thus, those texts in which we find the Son described as caused or created “we are to refer to the humanity [assumed by the Son], but all that is absolute and unoriginate we are to reckon to the account of his Godhead.

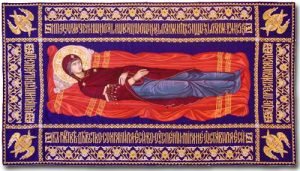

Gregory lays down a crucial principle in his biblical analysis of Proverbs 8:22, “The Lord created me at the beginning of his ways with a view to his works.” Many early Christian exegetes (scholars who study the meaning of biblical texts) saw this text as pointing to the divine Word, “the true Wisdom.” If so, the text appears to text appears to teach that the Son was created, a problem for all who would affirm his timeless, eternal nature. Gregory solves the difficulty by teaching that when biblical texts such as Proverbs speak of the Son as caused or created, they are referring to the economy/dispensation of salvation. The Son, God’s Wisdom, is sent by the Father “with a view to his works,” that is, “our salvation.” Thus, those texts in which we find the Son described as caused or created “we are to refer to the humanity [assumed by the Son], but all that is absolute and unoriginate we are to reckon to the account of his Godhead. This weekend, as I had indicated in the Bulletin last week, we also celebrate the feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God. It is a Marion Feast and, because it is our predominant celebration we still include the resurrection of Christ. We only include this feast in our weekend celebration so that we can celebrate it as a community. Why even do this? The feasts of Mary reinforce what we know about human life through the feasts of Jesus. The Church has purposely established six major feasts of Mary so that we know that what God revealed through Jesus is for both men and women. The Jesus message is for both men and women.

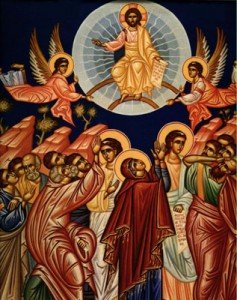

This weekend, as I had indicated in the Bulletin last week, we also celebrate the feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God. It is a Marion Feast and, because it is our predominant celebration we still include the resurrection of Christ. We only include this feast in our weekend celebration so that we can celebrate it as a community. Why even do this? The feasts of Mary reinforce what we know about human life through the feasts of Jesus. The Church has purposely established six major feasts of Mary so that we know that what God revealed through Jesus is for both men and women. The Jesus message is for both men and women.

Jesus Christ is “the Way, the Truth and the Life” (John 14:6). He speaks the words of God. He does the work of God. The person who obeys Christ and follows His way and does what He does, loves God and accomplishes His will. To do this is the essence of spiritual life. Jesus has come that we may be like Him and do in our own lives, by His grace, what He Himself has done.

Jesus Christ is “the Way, the Truth and the Life” (John 14:6). He speaks the words of God. He does the work of God. The person who obeys Christ and follows His way and does what He does, loves God and accomplishes His will. To do this is the essence of spiritual life. Jesus has come that we may be like Him and do in our own lives, by His grace, what He Himself has done. On Tuesday of this coming week, our Church celebrates the Feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God – Her Falling Asleep. Tradition tells us that when the apostles opened the grave for St. Thomas to pay his respects (You will recall that he was absent when Jesus first appeared to the apostles after His death), her body was not there, only the funeral clothes in which the body had been wrapped. The Apostles realized then that Mary had been taken up body and soul into heaven.

On Tuesday of this coming week, our Church celebrates the Feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God – Her Falling Asleep. Tradition tells us that when the apostles opened the grave for St. Thomas to pay his respects (You will recall that he was absent when Jesus first appeared to the apostles after His death), her body was not there, only the funeral clothes in which the body had been wrapped. The Apostles realized then that Mary had been taken up body and soul into heaven.