It was not until the fourteenth century that the Byzantine Liturgy reached the full term of its development and a process of consolidation was under way. Local variations in practice continued to exist in the world of Byzantine Christianity. But the widespread influence of the Diataxis of Philotheos helped to establish a basic uniformity in the celebration of the Liturgy in all the churches of the Byzantine commonwealth.

Philotheos was a monk of Mount Athos who became Patriarch of Constantinople in 1354. Two rival Typika, or sets of rules for celebrating the services of the Church, were in use in the city. The traditional Typikon of the Great Church was that which originated in the ninth century in the monastery of St. John of Stoudios. But by the twelfth century the Typikon of the monastery of St. Sabas near Jerusalem was gradually gaining ground, not least because it gave more detailed instructions for the celebration of the services.

While still on the Holy Mountain, Philotheos drew up two Diataxeis, one regulating the priest’s and deacon’s part in Matins, Vespers and the Liturgy, and one giving detailed directions for the celebration of the Liturgy. It established the text of the rites as well as the ceremonial to be observed. Its widespread use brought a uniform order into the Liturgy, particularly in the performance of the prothesis (i.e., proskomedia or the rite for preparing the gifts), which had the largest number of variations It was introduced into the Great Church when Philotheos became Patriarch and quickly spread to the Slav as well as the Greek Churches. Its rubrics (i.e., guidelines for performing the ritual) were incorporated into the first printed service books in the sixteenth century.

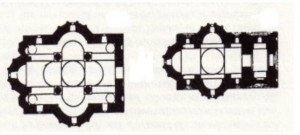

By the fourteenth century the cross-in-square planned church was still widely found, but now alongside other designs. The Greek cross shape returned, and basilican-style churches were built too. Each part of the Byzantine world evolved its own characteristic variants of the basic themes, and a good many churches of the twelfth to fifteenth centuries have survived to enable us to study the setting in which the Liturgy was, and continues to be, celebrated. Many still have some or all of their decoration. The domed nave and the three apses at the east end continued to be normal.

By the fourteenth century the cross-in-square planned church was still widely found, but now alongside other designs. The Greek cross shape returned, and basilican-style churches were built too. Each part of the Byzantine world evolved its own characteristic variants of the basic themes, and a good many churches of the twelfth to fifteenth centuries have survived to enable us to study the setting in which the Liturgy was, and continues to be, celebrated. Many still have some or all of their decoration. The domed nave and the three apses at the east end continued to be normal.

It should be noted that the Liturgy is best performed in a building that is structured to enhance and support the ritual rather than a building that is shaped without regard for the ritual. The Byzantine ritual was highly developed. Everything was in harmony – building and ritual!