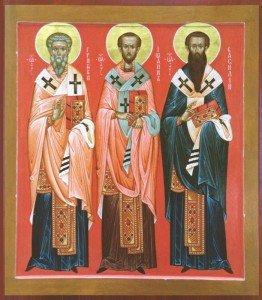

Perhaps three of the most influential Eastern Fathers of the Church were the Cappadocian Fathers: Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa (Basil’s brother) and Gregory Nazianzus. They advanced the development of Christian Trinitarian theology, especially our understanding of the Holy Spirit. Hopefully their names come as no surprise to persons who have been reading my Bulletins on a regular basis.

Perhaps three of the most influential Eastern Fathers of the Church were the Cappadocian Fathers: Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa (Basil’s brother) and Gregory Nazianzus. They advanced the development of Christian Trinitarian theology, especially our understanding of the Holy Spirit. Hopefully their names come as no surprise to persons who have been reading my Bulletins on a regular basis.

The early Christian understanding of creation and of man’s ultimate destiny is inseparable from pneumatology (study of spiritual beings, especially in Christianity the study of the Holy Spirit); but the doctrine of the Holy Spirit in the New Testament and in the early Fathers cannot easily be reduced to a system of concepts. The fourth-century Christian discussions on the divinity of the Spirit remained in a soteriological (salvation), existential context. Since the action of the Spirit gives life in Christ, He cannot be a creature but is consubstantial with the Father and the Son – He is of the same substance as the Father and the Son.

You will recall the when attempting to identify Jesus, the Fathers likewise asserted that He, Jesus, is also of the same substance (consubstantial) with the Father. This argument was used both by Athanasius and by Basil. The writings of these two Fathers remained, throughout the Byzantine period, the standard authorities on the Holy Spirit. Except in the controversy around the Filioque – a debate about the nature of God rather than about the Spirit specifically – there was little development in the conceptual understanding of the Holy Spirit – in the Byzantine Middle Ages. This does not mean that the experience of the Spirit was not emphasized with greater strength than in the West, especially in hymnology, in sacramental theology and in spiritual literature.

Basil writes, “As he who grasps one end of a chain pulls along with it the other end to himself, so he who draws the Spirit draws both the Son and the Father along with It.” This passage, quite representative of Cappadocian thought, implies first that all major acts of God are Trinitarian acts, and secondly that the particular role of the Spirit is to make the first contact, which is then followed – existentially, but not chronologically – be a revelation of the Son and, through Him, of the Father. The personal being of the Spirit remains mysteriously hidden, even if He is active at every step of divine activity.

More to follow about the Spirit