I have been attempting in this article to convey the Eastern Liturgical idea of the Divine Liturgy being anamnetic in character, that is experiencing the past as truly present – an occasion wherein participants can experience the real presence of God. It seems that in the 4th century, when Arianism was being fought by right-believing Christians, St Basil the Great began using a doxology to protest the Arian interpretation of the one commonly in use. The one that Arians misinterpreted was: “to God and Father with the Son together with the Holy Spirit. St Basil, instead, introduced this doxology: to God and Father, through the Son in the Holy Spirit.

The Eastern theologians, St. Basil included, energetically defended the divinity of Christ, in the sense of a consubstantiality with the Father, against the Arians. Remember that the Arians didn’t believe that Christ was equal and of the same substance as the Father. At the same time, when the discussion turned to the mediatorship of Christ, they focused their attention on the historical work of redemption. Statements of scripture and tradition about a subordination of the Son to the Father could thus be understood in terms of the Lord’s earthly life and related solely to his humanity.

After Basil’s reform of the doxology, the priestly action of Jesus as the here and now active mediator of our prayers and sacrifices – an action that had formerly been the object of keen Christian awareness – was increasingly obscured; the priestly activity of Jesus was increasingly located in his past work of redemption. In consequence, there was also an increasing emphasis on the Liturgy as a re-presentation, or making present, of the past saving act of Jesus.

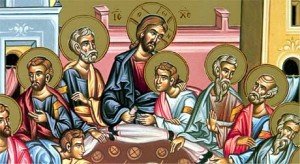

“The anamenetic character of the Lord’s Supper was seen as the means of making the past saving act present to us and giving all subsequent followers of Jesus – the Church – a share in redemption.

The greater stress on the general anamnetic character of the eucharistic celebration led inevitably to a richer development of the anamnesis as a particular prayer. This development cannot be missed in the liturgies of the fourth century. The anaphora of His had said simply: “Mindful of his death and resurrection we offer you the bread and cup”. I will continue to explore more about anamnesis