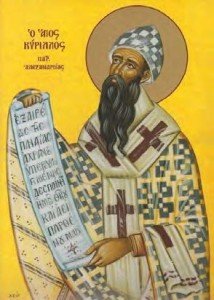

I would continue sharing Cyril’s ideas about Christ as Savior in the East. There is no doubt that Cyril used ambiguous terminology (like his formula one nature incarned of God the Word, which he unknowingly borrowed from Apollinaris), but his rejection of Nestorianism was motivated not by any “anthropological minimalism” but, on the contrary, by the conviction that human destiny is linked with communion with God – an ultimately maximalist view of humanity.

Nestorianism consisted, on the contrary, in a rationalizing sense of incompatibility between the divine and the human: the person of Christ, in which divinity and humanity met, appeared as a juxtaposition of two mutually impermeable entities. According to Nestorius, the human nature of Christ kept not only its identity but also its autonomy. Christ’s birth and death were human only. Mary was mother “of Jesus,” not “of God.” Jesus the “Son of man” died, not “the Son of God.” It was this duality, which implied a different anthropology, that Cyril rejected. On the other hand, he simply could not remain logical with himself if he adopted a doctrine similar to that of Apollinaris or Julian. It is precisely because Christ accepted, complete humanity – in an incomplete, unfulfilled state, from which it need to be saved – that the divine Logos had to assume suffering and death. He did this in order to lead humanity to incorruptibility through the resurrection. He first came down where incomplete humanity truly was – “in the depth of the pit” – and then cried before dying, “My God, why have you forsaken me.” This moment was indeed “the death of God”: the assumption by God himself, in an ultimate act of love, of humanity in its state of separation from its truly “natural” communion with God. Christ’s humanity was, therefore, neither diminished nor limited: it was humanity in its very concrete incompleteness.

Hopefully you, my readers, are beginning to see how Cyril and, of course, other Greek Fathers of the Church struggled to find the right way to truly express the great mystery of God’s unique incarnation as a man in the Person of Jesus. How we express this great mystery makes all the difference.

It is obvious that some aspects of Cyril’s Christology needed to be more clearly defined. In 451 the Council of Chalcedon affirmed the doctrine of Christ’s two natures in their real distinctiveness and the doctrine of a hypostatic (not a “natural”) union of the two natures.

Think about this!