What is universally verifiable is that the core of the primitive liturgy has, throughout its development, always remained the same.

I would now like to take a closer look at the general characteristics of the byzantine Eucharistic Liturgy that we presently use. The focus is on the last two periods of liturgical history, which, for the Byzantine tradition, extends from the end of the 4th century until the beginning of the 16th century. Because of his writings, our first witness to the form of the Byzantine Liturgy and its uses is St. John Chrysostom, (397-404). He attests to the form of the Liturgy. It was not until the beginning of the 16th century, that is 1526, that the first printed copy of the Liturgy was produced. It was the invention of the printing press and not the intervention of a bishop or synod, that was responsible for the final unification of liturgical usage in the Byzantine East.

Of course one must not picture this unification in rigid, Tridentine categories, for in the East there is not such thing as a “typical” liturgical book, i.e., an official liturgical text obligatory on all. Nor did the advent of printing mark the end of growth and local adaptation. But since then the developments are so easy to trace that liturgical history ceases to be a scholarly problem and so becomes relatively uninteresting except as a mirror of local customs, minor variations on an already well-known theme. The Byzantine Divine Liturgy can be characterized as the Eucharistic service of the Great Church – of Hagia Sophia, the cathedral church of Constantinople – as formed into an initial synthesis in the capital by the 10th century, and then later modified by monastic influence. This is not a truism, to say that the Byzantine Eucharist is the rite of Constantinople. There is nothing “Roman” about the Roman rite and nothing “Byzantine” about the present Byzantine Divine Office, which comes from the monasteries of Palestine, and replaced the Office of the Great Church after Constantinople fell to the Latins in the Fourth Crusade (1204).

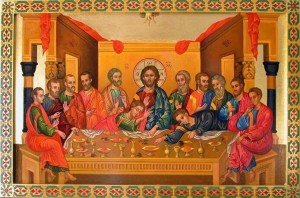

Perhaps the most striking quality of the Byzantine Liturgy that has evolved from the eucharist service of the Hagia Sophia is its truly opulent ritualization, a ceremonial splendor heightened by its marked contrast to the sterile verbalism of so much contemporary Western liturgy.

I think most will agree with this!