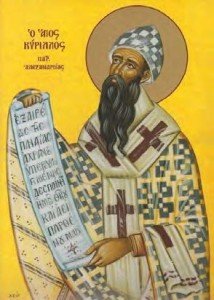

I have been sharing the ideas of both Athanasius and Cyril about Jesus. They saw Him as Perfect God and Perfect Man and the Council of Chalcedon affirmed their understanding.

If Athanasius and Cyril, by defending the divinity of Christ and the unity of His being, provided Christian spirituality with its essential basis, their names and their messages remained somewhat controversial even after their death. One of the major reasons for the bitter theological debates that followed was that zealous followers of the two great masters tended to freeze their doctrines into verbal formulas. These were accepted literally and out of the context provided by the spiritual experience of the catholic (i.e., universal) tradition and the theology of the masters themselves. The struggle of Athanasius cen-tered on the Nicaean creed and, in particular, the Greek term homoousios (translated as consubstantial), used in that creed to affirm the common divine “essence” of the Father and the Son. But the same term was used by Sabellians (Sabellianism in the Eastern Church or Patripassianism in the Western Church) who interpreted “consubstantiality” as incompatible with the Trinitarian revelation of God. For Sabellians, to say that the Father and the Son are of “one essence” meant that God was not three persons, but a unique essence with only three aspects or “modes” of manifestation. Thus the Nicaean and Athanasian formulation of the Christian experience – true as it was in its opposition to Arianism (an influential heresy denying the divinity of Christ, originating with the Alexandrian priest Arius ( circa 250 – circa 336). Arianism maintained that the Son of God was created by the Father and was therefore neither coeternal with the Father, nor consubstantial) – needed further terminological and conceptual elaboration. This elaboration was provided by the Cappadocian Fathers with their doctrine of the three divine Hypostases, or really distinct persons. It did not truly imply any disavowal of Athanasius but a more sophisticated use of Greek philosophical terms. Paradoxically, the Cappadocians, who were better versed than Athanasius in ancient Greek thought, were more successful than he was in showing the incompatibility between biblical trinitarianism and Greek philosophical categories. But they did so by using Greek vocabulary as a tool, changing its meaning and making it into a manageable instrument of Christian witness.

The process of our faith has been truly guided by God’s Spirit.