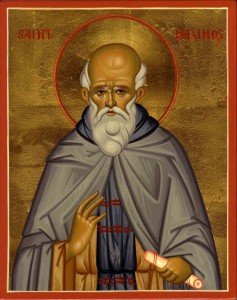

Another Greek Father of the Church that was greatly responsible for how we view Christ and the Holy Spirit, is Maximus the Confessor. Maximus’ place in the history of Christian Doctrine is primarily associated with his defense of Chalcedonian orthodoxy against Monotheletism (the belief that Christ had only one divine-human “will”). As you may recall, the Council of Chalcedon clearly stated that Christ, since He had two natures, namely Divine and Human, had to have two wills. Christ only had one personality which united His two natures but, in doing that, one nature did not have power over the other. Indeed, for Maximus, real humanity is dynamic, creative and endowed with a proper “energy”: this was, indeed, the case with the humanity of Christ, who, being a man, possessed a human will distinct from the divine. This human will of Christ was in conformity with the eternal purpose of God. Christ is the archetype of humankind. In monotheletism, the humanity of Christ, although accessible to “contemplation”, did not possess any “movement” or energy proper to itself, and the Chalcedonian definition, which affirmed that “the characteristic property of each nature of Christ was preserved” in the hypostatic union, had lost its meaning. The merit of Maximus was, therefore, in having decisively counteracted a monophysitic trend which interpreted deification as an absorption of humanity into divinity. For Maximus, deification was to be seen not as a denial but as a reaffirmation of created humanity in its proper and God-establish integrity.

However, Maximus at no point of his system was renouncing the essential message of Cyrillian Christology. God became human, he always affirmed, so that

…whole people might participate in the whole God and that in the same way in which the soul and the body are united, God would become partakable of by the soul, and through the soul’s intermediary, by the body, in order that the soul might receive an unchanging character and the body, immortality; and finally, that the whole human being would become God, deified by the grace of God become man – whole man, soul and body, by nature – and becoming whole God, soul and body, by grace.

As in the case of Cyril, the union between the “whole” God and the “whole” human being did not imply, for Maximus, any real absorption of humanity.

Remember, we’re talking about a great mystery!