There are several truly great challenges in our Christian faith, namely the belief in God as Three-In-One, the two-fold nature of Jesus as both God and Man, and, of course, the real presence of Christ in bread and wine that is transformed by the power of God through our prayers. I think that once we embrace in faith these three great mysteries, the other profound mysteries that are a part of our faith seem easy to accept.

There are several truly great challenges in our Christian faith, namely the belief in God as Three-In-One, the two-fold nature of Jesus as both God and Man, and, of course, the real presence of Christ in bread and wine that is transformed by the power of God through our prayers. I think that once we embrace in faith these three great mysteries, the other profound mysteries that are a part of our faith seem easy to accept.

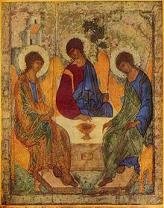

During the last several issues of this article I have been sharing the thoughts and ideas that the Fathers of the Church struggled with in order to come to the profound idea that our God is truly Three-In-One. He is the Holy Trinity Who we call Father, Son and Holy Spirit. All Three Persons are of the same, one substance and yet distinct in their Personhood. It was a question of finding a distinction of terms which could express the unity of, and the differentiation within, the Godhead, without giving the pre-eminence either to the one or to the other. The Fathers of the fourth century found two Greek terms that they believed could lead intellect towards the mystery of the Trinity. The two important terms are ousia (οὐσία) and hypostasis (ὑπόστασις). Its called the Cappadocian solution to the Trinitarian controversy of the fourth century. That solution is summarized in the phrase ‘one ousia, three hypostaseis’ (one essence and three persons). While often presented as widely employed and greeted with relief and enthusiasm, this phrase, as such, is rare in the writings of the Cappadocian Fathers and may not be the best short expression of their teaching on the Trinity. The distinction in meaning between ousia and hypostasis (both of which mean something that subsists) was worked out only in the late fourth century, and was, to some writers, less than convincing.

Another tradition attempted a solution, which was called miahypostatic theology, which was more widely and forcefully represented than is usually assumed. Its most visible proponent was Marcellus of Ancyra, but it is found to some extent in Athanasius, in many other Egyptian bishops and in much of the West. In the course of the fourth century, the miahypostatic tradition, which first appears as a late form of monarchianism, gave up all of its distinctive contours except one: it would not accept the phrase ‘three hypostaseis’ as orthodox faith.

Our faith born out of great debate and struggle.