In the previous issue of this article, I truly began sharing the role of Christ as Savior as seen in the East. Our Eastern Church has, of course, seen this slightly different than the Church in the West. One is not right and the other wrong. The difference allows us to brace a way that responds to our individual spirits. Rather than being closed, our Christian faith is truly open to quite different approaches to the same goal, salvation.

Since the beginning of the Church, the Fathers have had different ideas, and opinions about our faith. Both have agreed that God came as a real human person to serve as a model of how we might accomplish the purpose of life, that is our personal transformation into truly spiritual-human beings created in the likeness of Jesus Christ, who is God Himself incarnate.

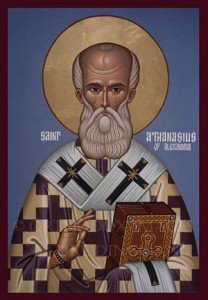

For Athanasius, salvation is an establishment of fellowship and communion between God and us, humankind. Why? Because anything less that such a fellowship would imply a limitation of divine love. Hence his famous definition of salvation as “Theosis” or “deification” which became a standard of Greek patristic thought.

The affirmation of Christ’s divinity in Nicaean and Athanasian categories inevitably raised the questions concerning the historical Jesus as man. The issue involved long debates, schisms and a search for appropriate definitions at councils – Ephesus (431), Chalcedon (451), Constantinople II (553), Constantinople III (680) and Nicaea II (787). The result was a commitment to a single Christological dogma in the East and in the West, although differences remained in the spiritual vision of the reality of the “life in Christ.” At the center of these debates stood the figure and the teaching of Cyril of Alexandria (d. 444), who should not be unfamiliar to anyone reading my Bulletins.

Before Cyril of Alexandria had engaged himself in bitter theological debates with Nestorius (428-31), the basic inspiration of his understanding of the Christian mystery appeared in his serene and noncontroversial exegetical writings, particularly his interpretation of the Gospel of John and his commentaries on other New Testament writings. Here Cyril’s main concern was not to provide his readers with a rational scheme of the incarnation but to express its kerygmatic meaning: God, who “alone has immortality”, is the only Savior from corruption and death.