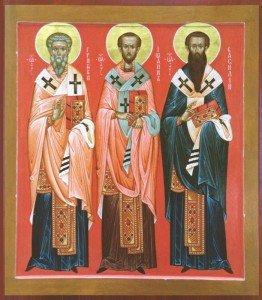

I shared, in the last issue of this article, that the Cappadocian Fathers used ancient Greek thought to clarify the ideas of Athanasius about who Christ is. They accomplished this by using Greek, philosophical vocabulary as a tool, changing its meaning and making it into a manageable instrument of Christian witness. An example of this is how they used of the Greek words homoousios and hypostases (which I hope my regular readers already come to know).

I shared, in the last issue of this article, that the Cappadocian Fathers used ancient Greek thought to clarify the ideas of Athanasius about who Christ is. They accomplished this by using Greek, philosophical vocabulary as a tool, changing its meaning and making it into a manageable instrument of Christian witness. An example of this is how they used of the Greek words homoousios and hypostases (which I hope my regular readers already come to know).

The same – actually almost identical – process took place in the fifth century after the triumph of Cyril over Nestorius. This process is connected with the famous decree of the Council of Chalcedon (451). Cyril’s Christology has been both kerygmatic and polemical. Eutysches – a zealous, ultra-Cyrillian ascetic – interpreted the unity of divinity and humanity of Christ to mean that humanity was so totally “deified” that it ceased to be “our” humanity. According to him, Christ was certainly “consubstantial” with the Father, but not “with us.” His humanity was absorbed by God. Eutyches was formally faithful to the Christology of Cyril, but in fact he was depriving it of its meaning for human salvation: God, according to Eutyches, was not sharing human destiny – human birth, human suffering, human death itself – but, while remaining absolute, changeless and transcendent, was absorbing that human identity which he had originally created. Was he then still the God of love?

Hopefully my readers are coming to understand that the struggle that existed in the early Church was to come to an acceptable (orthodox) understanding of WHO JESUS IS. The understanding of Eutyches was, of course, found to be false. The Council of Chalcedon (451) came as a reaction again Eutyches’ expression of who Jesus is. But the Council’s statement of Who Christ is was a rather elaborate formula which resulted from long debates and was intended to satisfy the different existing terminological traditions: the Alexandrian, the Antiochene and the Latin (these were the three main schools of theological thought). The latter expressed itself in the powerful intervention of Pope Leo the Great in his letter to Flavian of Constantinople. In this famous text, the pope, using a terminology inherited from Tertullian and Augustine, carefully established the integrity of the two natures of Christ, and insisted that this integrity requires that each nature preserve its characteristics.