In the last issue of this article, I began to share with you the Liturgy as it was described in the Apostolic Constitutions. As I shared, after the entrance into the worship space, readings took place. The readings were followed by a teaching or reflection by the bishop or priest. Then the Great Litany was proclaimed. This litany was followed by prayers for those preparing to be baptized. After these particular prayers, non-baptized persons were dismissed and the Creed was said.

After the Creed was said, deacons brought the gifts to the bishop who had processed to the altar. There is no mention in the Apostolic Constitutions were the gifts came from or how they were provided. But it is probable that people brought bread and wine to the worship space with them and left them in areas outside the worship space. It has been observed that the deacon’s admonitions would come more logically after the bringing in of the bread and wine. But liturgy is not always logical: though it is quite possible that the compiler of the Apostolic Constitutions has here put his sources together clumsily.

The rubric preceding the Anaphora sets the scene for the eucharistic prayer:

The rubric preceding the Anaphora sets the scene for the eucharistic prayer:

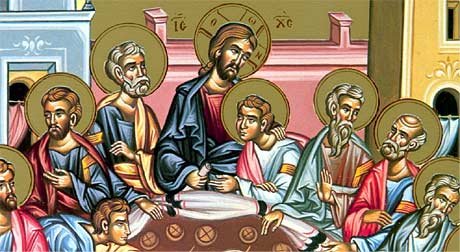

And let the priests stand on the bishop’s right and on his left, as disciples standing by a teacher. But let two deacons on either side of the altar hold a fan of thin tissue or of peacock’s feathers, and let them gently ward off the small flying creatures, so that they may not approach the cups.

The priests still have their proper place as the real Clement of Rome described it at the end of the first century:

Then let the bishop, after praying by himself together with the priests, and putting on a splendid vestment, and standing at the altar, and making the sign of the cross with his hand upon his forehead say: ‘The grace of the Almighty God, and the love of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the communion of the Holy Spirit, be with you all.’

In the fourth century all the prayers of the Liturgy were public prayers. That is why we have returned to saying many of the previously private prayers out loud. It was never intended that any of the prayers would be private except the prayer for the priest before the Anaphora.

It was no doubt natural for the clergy to pray in preparation for the Eucharist. But their prayer was silent and informal. St Paul’s prayer at the end of his Second Epistle to the Corinthians became the characteristic introduction to Eastern anaphoras. In the Clementine Liturgy it was followed by the exhortation: Lift up your minds! The response was: We lift them up to the Lord. Then the priest said: Let us give thanks to the Lord. Reponse: It is meet and right.