TOPIC: CHRISTOLOGY

By Len Mier

TOPIC: The heresy of Arius and how this heresy was dealt with by the Fathers of the First Ecumenical Council (Nicaea 325 CE)

There has been a struggle in Christianity from its very beginning as to who and what Jesus of Nazareth is. Even while Jesus was alive and with his disciples there seems to be a need to clarify the disciples’ belief. It is in Matthew’s Gospel that Jesus himself asked this question, “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” and then asks of His disciples, “But who do you say that I am?” Peter’s response, “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” This seems to leave more questions than it does answers. The Church struggled for over three hundred years trying to make sense of what the statement “Jesus is the Son of the living God”, means. It was only after the acceptance of the Christian faith, and the need for a unified statement of belief at the command of the first Christian emperor, did the whole Church tackle this issue.

There has been a struggle in Christianity from its very beginning as to who and what Jesus of Nazareth is. Even while Jesus was alive and with his disciples there seems to be a need to clarify the disciples’ belief. It is in Matthew’s Gospel that Jesus himself asked this question, “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” and then asks of His disciples, “But who do you say that I am?” Peter’s response, “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” This seems to leave more questions than it does answers. The Church struggled for over three hundred years trying to make sense of what the statement “Jesus is the Son of the living God”, means. It was only after the acceptance of the Christian faith, and the need for a unified statement of belief at the command of the first Christian emperor, did the whole Church tackle this issue.

Prior to the First Ecumenical Council, the understanding of who this person Jesus is ran a wide spectrum of understanding. In the Pre-Nicaean church the spectrum of understanding went from those who said Jesus is a created Being adopted by God the Father in some special way, for example made holy by being inhabited within his flesh by an angel. It is by this adoption He was the Son of God. At the opposite end of this spectrum are those who said that God, being pure unchanging spirit, came into this world and cast what humans see as human form and appearance but was not like us in the flesh. Eventually orthodoxy tried to reach a correct understanding of who Jesus is. The concept of the Logos or as found in St. John’s Gospel the Word Made Flesh was seen as a frame-work for this understanding. Although this middle ground made clearer our understanding, it still lacked an explanation of Jesus and His relationship to the Father and within the Trinity.

It is in the fourth century that one of the strongest and most continuing heresies in the Church emerges and takes shape. Its primary center of teaching was the Church of Alexandria in Egypt. From there it spread east to Palestine and Syria eventually throughout the Eastern Roman Empire. This heresy is called Arianism, which is named after one of its strongest supporters, Arius, a priest in Alexandria. It was Arius’ expulsion from the city of Alexandria that aided in the spread of this heresy. It was not that Arius denied that Jesus was the Son of God, he did seem to believe in that teaching. His teaching is more of an error in thinking on the nature of the Trinity and Godhead and how Jesus related to God the Father and his equality with the Father.

I would submit for your consideration that, while Arianism is an error in thinking, it has negative consequences as to the nature and salvific vocation/work of Jesus Christ. This heresy jeopardizes the union of the human with the Trinitarian God.

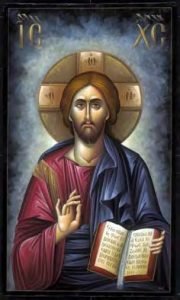

The key to Arius is the idea of “the unbegotten” and unequal to God the Father. God is the only thing that is unbegotten, uncreated and eternal. Scripture, Arianism says, Eludes that the Logos, being begotten from the Father, cannot be true God. The argument Arius puts forth is that the Logos was a creature the “first creation” of the Father and a perfect creation participating in the Godhead, but a creation none the less not being equal to the Father. Some scripture quoted by Arius and his followers to support his argument are John 14:28 “The Father is greater than I” and St. Paul’s letter to the Colossians 1:15 “the first-born of all creation” and from the Old Testament book of Proverbs 89:22 “The Lord created me a beginning of his ways”. The theology when placed within the philosophical climate of the period makes Jesus appear to be a demi-god in adaption of Hellenistic philosophy and pagan thinking. Open conflict between bishops and individual churches began to cause divisions within the Church. This did not go unnoticed by Constantine. The emperor wanted a unified church and peace established within his empire. To settle this argument Constantine called the Bishops to gather in an Ecumenical council to take place in Nicaea, a city near the capital. He guaranteed safe passage to all those who would participate, hoping to encourage maximum participation of all the bishops of the Church.

The question that was to be debated, what is the nature of the Son of God and his relation to God the Father? The hope was for a statement of belief on the issue and the ability to come to an acceptable understanding of the question.

Because scripture is deficient for a full explanation of this question, the Fathers turned to the use of a philosophical understanding of God to settle this question. One of the main philosophical concepts that was brought for discussion was the idea of essence, in Greek ouisios. The term substance being used in the West giving rise to the Latin term consubstantial, the words essence and substance as I am using them have the same meaning. It can be understood as the expression “being made up of the same kind of stuff”. The philosophy of the time said there were two distinct essences. The first essence, that essence or substance which is not created, is not subject to change and is eternal. This is what we call God. The second essence that of the world or Cosmos, is changing and is created.

The debate hinged on two words in the understanding of Jesus and His relation to God the Father. Was Jesus of the same essence (homoousios) or was Jesus made of similar essence (homoiousios). The argument was eventually decided on the side of homoousios. The Fathers believed that Jesus was begotten of the Father in all eternity and not created in any way. They also stated that the essence of the person of Jesus was, in fact, the same essence as that of God the Father. This belief gives rise to the symbol of faith that orthodox Christians recite in the liturgy. The Nicaean Creed states our belief.

To be continued.

Genesis states that humans were created in the image of the Creator and, as the original text states, “according to the likeness of God.” The word translated ‘likeness’, homosiosis, suggests something more precise in Greek: the ending, -osis, imples a process, not a state (the Greek for likeness as a state would be homoioma). The word homoiosis would moreover have very definite resonances for anyone who had read Plato, who envisages the goal of the human life as homoiosis – that is likening, assimilation – to the divine. In the Theaetetus, Socrates remarks in a phrase very popular among some of the Fathers: ’flight [from the world] is assimilation to God so far as is possible’. So, to be created according to the image of God and according to His likeness suggests that we have been created with some kind of affinity for God which makes possible a process of assimilation to God, which is, presumably, the point of human existence.

Genesis states that humans were created in the image of the Creator and, as the original text states, “according to the likeness of God.” The word translated ‘likeness’, homosiosis, suggests something more precise in Greek: the ending, -osis, imples a process, not a state (the Greek for likeness as a state would be homoioma). The word homoiosis would moreover have very definite resonances for anyone who had read Plato, who envisages the goal of the human life as homoiosis – that is likening, assimilation – to the divine. In the Theaetetus, Socrates remarks in a phrase very popular among some of the Fathers: ’flight [from the world] is assimilation to God so far as is possible’. So, to be created according to the image of God and according to His likeness suggests that we have been created with some kind of affinity for God which makes possible a process of assimilation to God, which is, presumably, the point of human existence.

Our readings this weekend are again taken from St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans and St. Matthew’s Gospel. In Romans we hear these words of Paul: “Through him [Jesus] we have gained access by faith to the grace in which we now stand, and we boast of our hope for the glory of God.” He then reminds the Romans and us that “affliction makes for endurance, and endurance for tested virtue, and tested virtue for hope.” Paul ends this section of his letter by sharing this thought: “hope will not leave us disappointed, because the love of God has been poured out in our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us”.

Our readings this weekend are again taken from St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans and St. Matthew’s Gospel. In Romans we hear these words of Paul: “Through him [Jesus] we have gained access by faith to the grace in which we now stand, and we boast of our hope for the glory of God.” He then reminds the Romans and us that “affliction makes for endurance, and endurance for tested virtue, and tested virtue for hope.” Paul ends this section of his letter by sharing this thought: “hope will not leave us disappointed, because the love of God has been poured out in our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us”. In the last issue I shared information about how the present four gospels that make up the New Testament (NT) was finally chosen. These four gospels ac-quired importance because of the names attached to them: John was an important figure among the Twelve and in the church; Mark’s Gospel was related to Peter; Luke’s Gospel was related to Paul in some vaguer way; and the First Gospel was quickly related to Matthew, one of the Twelve. Of course the importance of the communities with which the Gospels were associated may also have figured in their survival. Matthew was probably directed to a Syrian community in the Antioch area. Mark was composed at Rome. Sometimes scholars relate Luke to Rome, sometimes to Greece. John was composed at Ephesus or in Syria.

In the last issue I shared information about how the present four gospels that make up the New Testament (NT) was finally chosen. These four gospels ac-quired importance because of the names attached to them: John was an important figure among the Twelve and in the church; Mark’s Gospel was related to Peter; Luke’s Gospel was related to Paul in some vaguer way; and the First Gospel was quickly related to Matthew, one of the Twelve. Of course the importance of the communities with which the Gospels were associated may also have figured in their survival. Matthew was probably directed to a Syrian community in the Antioch area. Mark was composed at Rome. Sometimes scholars relate Luke to Rome, sometimes to Greece. John was composed at Ephesus or in Syria. There has been a struggle in Christianity from its very beginning as to who and what Jesus of Nazareth is. Even while Jesus was alive and with his disciples there seems to be a need to clarify the disciples’ belief. It is in Matthew’s Gospel that Jesus himself asked this question, “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” and then asks of His disciples, “But who do you say that I am?” Peter’s response, “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” This seems to leave more questions than it does answers. The Church struggled for over three hundred years trying to make sense of what the statement “Jesus is the Son of the living God”, means. It was only after the acceptance of the Christian faith, and the need for a unified statement of belief at the command of the first Christian emperor, did the whole Church tackle this issue.

There has been a struggle in Christianity from its very beginning as to who and what Jesus of Nazareth is. Even while Jesus was alive and with his disciples there seems to be a need to clarify the disciples’ belief. It is in Matthew’s Gospel that Jesus himself asked this question, “Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” and then asks of His disciples, “But who do you say that I am?” Peter’s response, “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” This seems to leave more questions than it does answers. The Church struggled for over three hundred years trying to make sense of what the statement “Jesus is the Son of the living God”, means. It was only after the acceptance of the Christian faith, and the need for a unified statement of belief at the command of the first Christian emperor, did the whole Church tackle this issue. I am sure that it has become quite obvious to all those who have consistently read my Bulletin and also this particular article, the “call to holiness” is a call to understand human life and why life is the way that it is. In fact the discovery of the meaning and the purpose of life is the particular goal for our present life on earth. Human life, as God created it, is first and foremost meant to be a time of learning about our relationship with God and the rest of creation. We can be sure that God had a “REASON” for creating us and the universe. We believe that all of creation came into existence in accordance with a Divine Plan. Creation did not come into existence by chance! There is too much order and design built into creation for it to have come into existence just by chance.

I am sure that it has become quite obvious to all those who have consistently read my Bulletin and also this particular article, the “call to holiness” is a call to understand human life and why life is the way that it is. In fact the discovery of the meaning and the purpose of life is the particular goal for our present life on earth. Human life, as God created it, is first and foremost meant to be a time of learning about our relationship with God and the rest of creation. We can be sure that God had a “REASON” for creating us and the universe. We believe that all of creation came into existence in accordance with a Divine Plan. Creation did not come into existence by chance! There is too much order and design built into creation for it to have come into existence just by chance. Our Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church is the largest of the Eastern Catholic churches that are in communion with Rome. Christianity was established among the Ukrainians in 988 by St. Volodymyr and follows the Christianity established by missionaries from Constantinople. It embraces rituals of the Byzantine Church. It also followed Constantinople in the Great Schism of 1054. Temporary reunion with Rome was effected in the mid-15th century. A definitive union was achieved at Brest-Litovsk in 1596, when Metropolitan Michael Ragoza of Kiev and the bishops of Vladimir, Lutsk, Polotsk, Pinsk, and Kholm agreed to join the Roman communion. The treaty guaranteed that the traditional rites be preserved intact. Orthodox Christians did not accept the union peaceably and the bishops of Lviv, Przemysl and the Orthodox Zaporozhian Cossacks actively opposed the Catholics. In 1633 the metropolitanate of Kiev returned to Orthodoxy while Lviv joined the union in 1677, followed by Przemyśl in 1692.

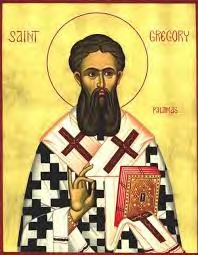

Our Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church is the largest of the Eastern Catholic churches that are in communion with Rome. Christianity was established among the Ukrainians in 988 by St. Volodymyr and follows the Christianity established by missionaries from Constantinople. It embraces rituals of the Byzantine Church. It also followed Constantinople in the Great Schism of 1054. Temporary reunion with Rome was effected in the mid-15th century. A definitive union was achieved at Brest-Litovsk in 1596, when Metropolitan Michael Ragoza of Kiev and the bishops of Vladimir, Lutsk, Polotsk, Pinsk, and Kholm agreed to join the Roman communion. The treaty guaranteed that the traditional rites be preserved intact. Orthodox Christians did not accept the union peaceably and the bishops of Lviv, Przemysl and the Orthodox Zaporozhian Cossacks actively opposed the Catholics. In 1633 the metropolitanate of Kiev returned to Orthodoxy while Lviv joined the union in 1677, followed by Przemyśl in 1692. Why, Gregory speculates, is our knowledge of God for the present fragmentary at best? His answered was that in this life we simply are too weak to view God’s nature and essence directly. Gregory held the hope that such will not always be the case. He refers to Paul’s words in first Corinthians that in the future “I will know fully, even as I have been fully known.”

Why, Gregory speculates, is our knowledge of God for the present fragmentary at best? His answered was that in this life we simply are too weak to view God’s nature and essence directly. Gregory held the hope that such will not always be the case. He refers to Paul’s words in first Corinthians that in the future “I will know fully, even as I have been fully known.” On this second weekend after Pentecost, our readings are taken from Paul’s Letter to the Romans and Matthew’s Gospel. With Pentecost the Church ends taking our readings from the Acts of the Apostles and John’s Gospel.

On this second weekend after Pentecost, our readings are taken from Paul’s Letter to the Romans and Matthew’s Gospel. With Pentecost the Church ends taking our readings from the Acts of the Apostles and John’s Gospel.