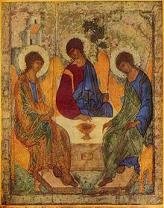

Use whatever word you wish: doctrine, teaching or tradition, they are all important to a healthy spirituality. Traditional Eastern teachings about the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation and the Church make it possible for us to really know God, or at least know Him in accord with our limited human intellects. They are so important because what you believe about God is going to affect how you think about Him, and thinking wrongly can really mess up an attempt to develop any kind of relationship. Eastern Christians are concerned about right believing, or correct doctrine, because we learned long ago that ignoring the directional signals leads us not to some king of freedom, but to a colossal train wreck.

For example, many people today like to think of Jesus in very human terms, placing Him in all kinds of modern settings – what would Jesus drive, or would He work at Wal-Mart – supposedly in order to get a better handle on how to understand His teachings today. Do the Nativity scene in modern dress and pretend He is just living next door to us; take Him some cookies when He moves in. This results in a dandy heresy known as Arianism; seeing Jesus as someone who is human enough, with some divine attributes, but not quite God. This heresy has been popular since the third century, and we slip into it all the time. The problem here is that a Jesus who isn’t God can’t really do much for us, other than invite us to barbeques and help u hang up the outdoor lights at Christmas. He certainly cannot save us; since he is not equal to the Father as God, he has no power to do so. If this kind of vision shapes your spirituality it makes having a relationship with Christ somewhat silly and sentimental rather than saving.

So a real part of our developing our spirituality is determining exactly what we believe about God, Christ and ourselves. It takes some reflection. Of course we know that it is difficult to understand Who God and Christ are since they are beyond our comprehension. We can, however, determine what we think THEY ARE NOT! They are not limited like us human beings!