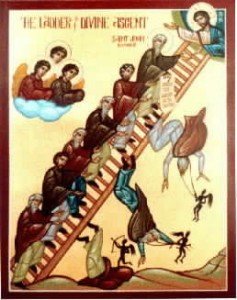

The tenth step on St. John’s Ladder is, as I shared in the last Bulletin, a sin called SLANDER. For what reason do we consider spiritual sins such as pride, hypocrisy, hatred and slander less grievous than “’physical” sins? A chaste virgin can be more defined in God’s eyes than an adulteress or a prostitute.

The tenth step on St. John’s Ladder is, as I shared in the last Bulletin, a sin called SLANDER. For what reason do we consider spiritual sins such as pride, hypocrisy, hatred and slander less grievous than “’physical” sins? A chaste virgin can be more defined in God’s eyes than an adulteress or a prostitute.

There is another reason that to pass judgment is to usurp shamelessly a prerogative of God: God alone knows the secrets of the heart. Often we see someone sinning and think we have seen the whole person, when in fact we have only caught a glimpse of him at his worst or at his weakest. We do not know whether that person has then shed tears in prayer and begged God for forgiveness. Unfortunately, we are keen to note people’s visible iniquities, but we are not so quick to consider their unseen repentance.

St. John tells us: Do not condemn. Not even if your very eyes are seeing something, for they may be deceived.

Let us note that stern warning: whatever sin of body or spirit that we ascribe to our neighbor we will surely fall into ourselves. Again, this reminds us of St. Paul’s words: In whatever you judge another you condemn yourself; for you who judge practice the same things! And, of course, if we have not yet committed the same sins (or, at least we think we haven’t), it is possible we will do so in the future.

Slander is a sin that Christians always try to justify. We say, I am not judging him, I’m just concerned for him. St. John calls this false love.

Slander is also a very infectious sin. Many of us find ourselves getting caught up in animated conversations about others, and not wishing to cause offense, we go along with it. We start contributing our own judgmental comments. Many Christians are not sure what to do when they find themselves in this situation. The advice, keep your big mouth shut!